Listening to people who have been referred to West Cheshire food bank, where I work, can be emotionally draining. How would you respond to a young girl who has been ripping out her own hair because she can’t cope? To a former soldier with a serious illness who is violently sick every time he takes his medication because you’re meant to take it on a full stomach?

Or to a mother, whose husband has left her, and now has no income and two children to look after? She’s starting a new job on Monday but won’t get paid for over a month. Until then, she has nothing.

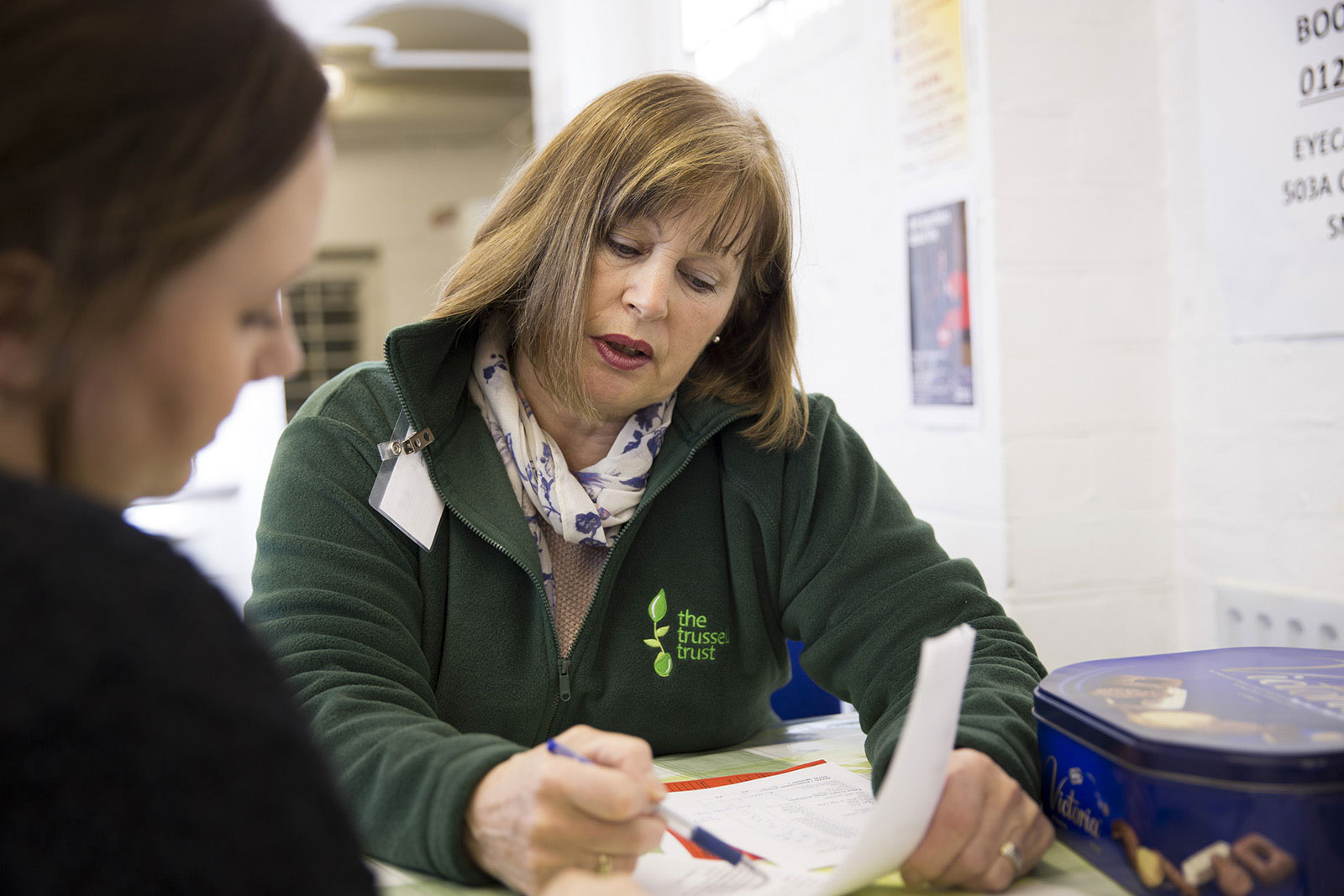

No one I’ve met wants to come to the food bank. It’s a last resort, adopted when other ways of coping in a crisis have been exhausted. Hundreds of people are referred to us every month and each one has a story to tell.

Robert had been working full-time and was receiving employment support allowance due to a leg injury. Before his appointment at a work-related activity group, he collapsed in town: the injury turned out to be a serious blood clot. He was rushed to hospital, missed the appointment and had his benefits stopped. He had to manage without any income for over five weeks and turned to the food bank.

Jane had been working as a probation officer when she escaped domestic violence. Pursued by her partner, she was forced to move a number of times and her mental and physical health deteriorated. Diagnosed with depression, a bowel disease and a chronic pain condition, she had to give up her job. She moved near to friends, sofa-surfing until she was able to manage her situation better. Jane finally submitted a homelessness application and was moved into supported accommodation, where staff referred her to a food bank, knowing she had no money for anything, even food.

Matthew attended his job-search programme on a Wednesday – a day earlier than scheduled for that week. He wasn’t told that he should have attended the following day instead. He had his benefits sanctioned, and couldn’t afford to top up his gas and electric meters. He turned to the food bank because he had no one to support him.

These stories are not exceptional. Many people are struggling in circumstances beyond their control, and are frequently unable to access sufficient food for between four and 13 weeks. The Trussell Trust reported this week that its food banks have had 1 million users over the past year, an increase of 19% from the previous 12 months, with experts saying this is “the tip of the iceberg”.

So why the rise? Research from Cheshire Hunger, Emergency Use Only and Below the Breadline point to three drivers: severe reductions in social security entitlement and levels, low-waged and insecure employment, and rising household expenditure, especially costs related to housing, utilities and food. Administrative delays paying benefits, punitive sanctions, benefit changes and employment and support allowance stoppages directly account for approximately half of referrals to our food bank. A further 20% are referred because of low, insecure income.

How do we move the increasingly noisy debate on food banks forward? The simple answer is that we must stop and listen. We must listen to the real, lived experiences of people who are going hungry. People struggling with poverty are the true experts on this, and it is their stories that must lead the way in finding a solution.

Alec Spencer, West Cheshire Foodbank Manager

This piece was originally published in The Guardian’s Opinion section on 23 April 2015.