UCL has always led on issues of significance to the nutritional health of the nation. Dr Jack Drummond, the first Professor of Biochemistry at UCL and former Dean of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, was the wartime Scientific Advisor to the Ministry of Food, which introduced food-rationing on the basis of his “sound nutritional principles”. It was essential work because a 1936 survey had suggested that half of the British population could not afford an adequate diet. Food poverty is a major public health concern again. One of its most visible symptoms is the number of people attending Foodbanks to receive emergency food aid. The Trussell Trust has reported that in the first 6 months of this year, referrals were up by 13% to 587,000 people, including 209,000 children.

At UCL, we did not know if these numbers told the whole story or were merely the tip of an unpleasant iceberg. One telephone survey had already suggested that the latter was the case.

We therefore used an experimental design to answer the question by including a control group of people who were on low incomes but were not destitute. The comparison between foodbank users and this control group could then be linked to the findings of the large National Diet and Nutrition Surveys which have reported on the nutritional health of the general population and of those on low incomes. This hierarchical approach was designed to put the scale of food poverty into a national context. For example, problems arising from a poor diet during early childhood are legion and lifelong and should be a matter of national public health concern.

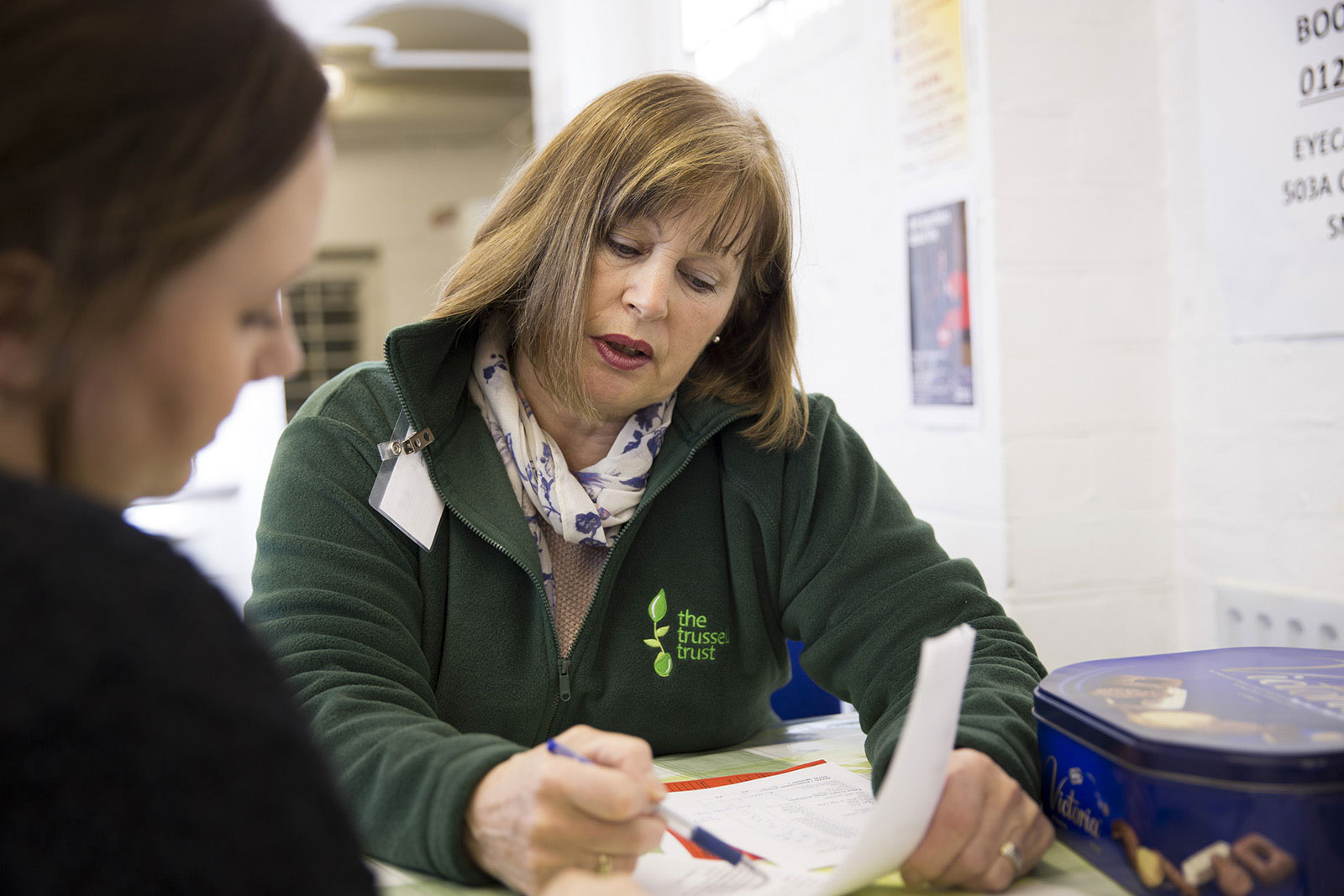

We recently released the findings of our study comparing the demographics and circumstances of 270 people seeking help from foodbanks, against 245 attending Advice Centres (AC) and Law Centres (LC) across three London boroughs (Islington, Wandsworth and Lambeth). The majority of foodbank, AC and LC clients report having low income and therefore often seek help from frontline crisis providers. ACs and LCs provide free advice and legal representation to their clients on a host of different issues including housing, immigration, money, and welfare support.

Our findings confirm a report released earlier this year from Kings College London and the University of Oxford, which found that foodbank users living in extreme poverty were vulnerable to income shocks, if there were unexpected events or expenses associated with them. We have also added ‘cold, hard facts’ to support the early report on “Emergency Use Only” which identified that ‘income crisis’ was the main driver of foodbank use. The authors identified the combination of ongoing financial strains and adverse life events as a cause of significant or total loss of income which led to destitution.

Today, we extend these ‘landmark’ studies and demonstrate that even those attending ACs and LCs are also at risk of being more food insecure if they are not receiving their benefits due to sanctions or delays, or have experienced serious life events in the past 6 mvonths.

What did we find?

We found that welfare-related issues were the most common reason to seek help from these front-line emergency services. This highlights that these charities have been a lifeline for those allowed to fall through the welfare ‘safety-net’, which is created as a last line of defence against destitution in the UK.

Our data showed that there was no such thing as a ‘typical foodbank user’ which distinguishes him or her them from the rest of the community, though a higher proportion of foodbank users taking part in this research were single adults, single parents or were homeless (including those living in temporary accommodation). One in three also had children living with them at home. Thus, it is likely that these children were not getting sufficient nutrients required for growth during crucial developmental stages.

We also found that living on a very low income, coupled with a sudden life event (e.g. relationship breakdown, illness, loss of benefits due to delays or sanctions) can throw someone into destitution. This also applies to those attending ACs and LCs when we pooled the analysis across the sample. Interestingly, food insecurity is common outside of the foodbank setting. We found that three out of four individuals attending ACs and LCs were food insecure, but less than 10% had been to a foodbank.

The three of us (myself and two MSc students who helped with data collection) met many participants who broke down in tears when completing our questionnaire. This required people to reflect on adverse events in their lives, on disrupted eating patterns and on their mental health. Some just could not believe that they now found themselves in a foodbank, as they had always worked hard for most of their lives. However, all of these cases just conveyed the sense of normality that nobody is immune to hard times, and anyone could find themselves in need of a foodbank.

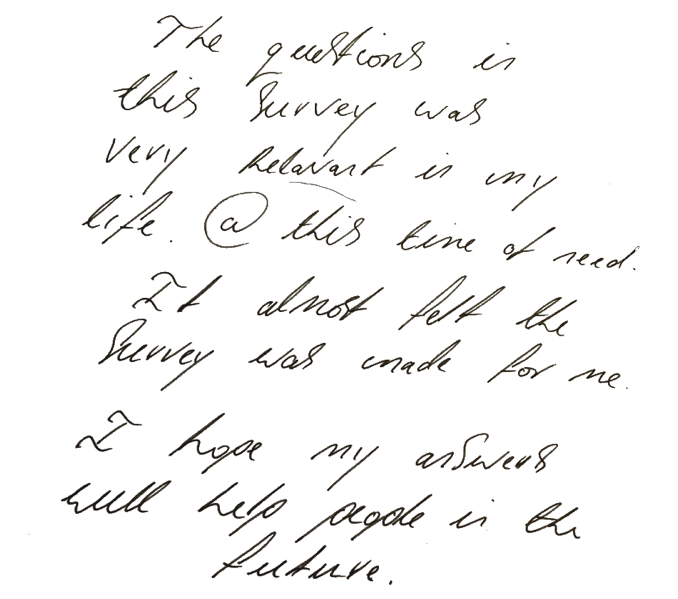

One person we spoke to, James (not his real name), commented on how the questionnaire made him reflect on the difficult period endured before his referral to a foodbank. This included relationship breakdown, struggling with mental health issues and food insecurity. Nevertheless, like many of our participants, they hoped that through their participation they would be able to raise awareness of what they had faced before they were referred to the foodbank.

So, what can be done?

From our data, the cause of food insecurity, and thus foodbank use, is ‘complex’. However, it does not mean it is too complex to be fixed, but it does require less debate and more concrete action to solve. As we found out, time and time again, behind these numbers there are people going through extremely hard times and experiencing hunger on a daily basis here in the UK.

Our data suggests that in the immediate term, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) should ‘pause and fix’ the problem with Universal Credit before it is rolled out. The specific problem is that there is a minimum waiting time of six weeks before the first monthly Universal Credit payment will be made. This waiting time is too long. Those coming to the foodbank have little to no financial resilience against the sudden loss of income caused by this waiting time.

We support the recent call for a national survey of food insecurity to understand the true scale of the problem. It is clear that foodbank use is a poor proxy for food insecurity, because fewer than 10% who were food insecure in ACs and LCs had been to the foodbank. Unless we know the scale of the problem, we will not know how to fix it.

Lastly, we welcome the effort to strengthen the relationship between foodbanks and advice and law centres. It can be seen that welfare and food insecurity were common issues across both populations. These charities have been a lifeline for those falling through the welfare ‘safety-net’. Yet, an increasing demand for their services means they may not be able to catch everyone who falls through to get the advice and legal representation they need. One of the ways to foster such collaboration is to extend the funding given to enable this cross-service collaboration.

About the project

- A copy of the paper is available upon request from the lead author: Edwina Prayogo [email protected]

- This research was a collaborative work between researchers at University College London (UCL) (Edwina, Prayogo, Dr George Grimble, Nurul Dina Rahmawati, and Thomas Waterfall), University of Southampton (Dr Mary Barker), University of Bath (Dr Sarah Chapman) and University of Bedfordshire (Dr Angel Chater). It was jointly funded by UCL Division of Medicine, Dr John Avanzini Ministries, and conceptualised through the initial grant from UCL Grand Challenges.